Received Pronunciation

Received Pronunciation (RP), also called the Queen's (or King's) English,[1] Oxford English,[2] or BBC English, is the accent of Standard English in England,[3] with a relationship to regional accents similar to the relationship in other European languages between their standard varieties and their regional forms.[4] Although there is nothing intrinsic about RP that marks it as superior to any other variety, sociolinguistic factors give Received Pronunciation particular prestige in England and Wales.[5] However, since World War II, a greater permissiveness towards allowing regional English varieties has taken hold in education[6] and in the media in England.

Contents |

History

The introduction of the term Received Pronunciation is usually credited to Daniel Jones after his comment in 1917 "In what follows I call it Received Pronunciation (abbreviation RP), for want of a better term."[7] However, the expression had actually been used much earlier by Alexander Ellis in 1869[8] and Peter DuPonceau in 1818[9] (the term used by Henry C. K. Wyld in 1927 was "received standard"[10]). According to Fowler's Modern English Usage (1965), the correct term is "the Received Pronunciation". The word received conveys its original meaning of accepted or approved – as in "received wisdom".[11] The reference to this pronunciation as Oxford English is because it was traditionally the common speech of Oxford University; the production of dictionaries gave Oxford University prestige in matters of language. The extended versions of the Oxford English Dictionary give Received Pronunciation guidelines for each word.

RP is an accent (a form of pronunciation) and a register, rather than a dialect (a form of vocabulary and grammar as well as pronunciation). It may show a great deal about the social and educational background of a person who uses English. Anyone using the RP will typically speak Standard English although the reverse is not necessarily true (e.g. the standard language may be pronounced with a regional accent, such as a Yorkshire accent; but it is very unlikely that someone speaking RP would use it to speak Scots or Geordie).

RP is often believed to be based on the Southern accents of England, but in fact it has most in common with the Early Modern English dialects of the East Midlands. This was the most populated and most prosperous area of England during the 14th and 15th centuries. By the end of the 15th century, "Standard English" was established in the City of London.[12] A mixture of London speech with elements from East Midlands, Middlesex and Essex, became known as RP.[13]

Usage

Researchers generally distinguish between three different forms of RP: Conservative, General, and Advanced. Conservative RP refers to a traditional accent associated with older speakers with certain social backgrounds; General RP is often considered neutral regarding age, occupation, or lifestyle of the speaker; and Advanced RP refers to speech of a younger generation of speakers.[14]

The modern style of RP is an accent often taught to non-native speakers learning British English[15]. Non-RP Britons abroad may modify their pronunciation to something closer to Received Pronunciation in order to be understood better by people unfamiliar with British regional accents. They may also modify their vocabulary and grammar to be closer to Standard English, for the same reason. RP is often used as the standard for English in most books on general phonology and phonetics and is represented in the pronunciation schemes of most dictionaries published in the United Kingdom.

Status

Traditionally, Received Pronunciation was the "everyday speech in the families of Southern English persons whose men-folk [had] been educated at the great public boarding-schools"[16] and which conveyed no information about that speaker's region of origin prior to attending the school.

- It is the business of educated people to speak so that no-one may be able to tell in what county their childhood was passed.

- A. Burrell, Recitation. A Handbook for Teachers in Public Elementary School, 1891.

In the 19th century, there were still British prime ministers who spoke with some regional features, such as William Ewart Gladstone.[17]

From the 1970s onwards, attitudes towards Received Pronunciation have been changing slowly. The BBC's use of announcers with strong regional accents during and after World War II (in order to distinguish BBC broadcasts from German propaganda) is an earlier example of the use of non-RP accents.

Phonology

Consonants

When consonants appear in pairs, fortis consonants (i.e. aspirated or voiceless) appear on the left and lenis consonants (i.e. lightly voiced or voiced) appear on the right

| Bilabial | Labio- dental |

Dental | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal1 | m | n | ŋ | |||||

| Plosive | p b | t d | k ɡ | |||||

| Affricate | tʃ dʒ | |||||||

| Fricative | f v | θ ð2 | s z | ʃ ʒ | h3 | |||

| Approximant | ɹ1, 4 | j | w | |||||

| Lateral | l1, 5 | |||||||

- Nasals and liquids may be syllabic in unstressed syllables.

- /ð/ is more often a weak dental plosive; the sequence /nð/ is often realised as [n̪n̪].

- /h/ becomes [ɦ] between voiced sounds.

- /ɹ/ is postalveolar unless devoicing results in a voiceless fricative articulation (see below).

- /l/ is velarised in the syllable coda.

Unless preceded by /s/, fortis plosives (/p/, /t/, and /k/) are aspirated before stressed vowels; when a sonorant /l/, /ɹ/, /w/, or /j/ follows, this aspiration is indicated by partial devoicing of the sonorant.[19]

Syllable finals /p/, /t/, /tʃ/, and /k/ may be preceded by a glottal stop (see Glottal reinforcement); /t/ may be fully replaced by a glottal stop, especially before a syllabic nasal (bitten [bɪʔn̩]).[19][20] The glottal stop may be realised as creaky voice; thus a true phonetic transcription of attempt [əˈtʰemʔt] may be [əˈtʰemm̰t].[21]

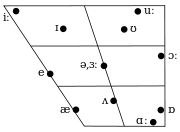

Vowels

| Front | Central | Back | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| long | short | long | short | long | short | |

| Close | iː | ɪ | uː | ʊ | ||

| Mid | e | ɜː | ə | ɔː | ||

| Open | æ | ʌ | ɑː | ɒ | ||

Examples of short vowels: /ɪ/ in kit, mirror and rabbit, /ʊ/ in put, /e/ in dress and merry, /ʌ/ in strut and curry, /æ/ in trap and marry, /ɒ/ in lot and orange, /ə/ in ago and sofa.

Examples of long vowels: /iː/ in fleece, /uː/ in goose, /ɜː/ in nurse and furry, /ɔː/ in north, force and thought, /ɑː/ in father, bath and start.

RP's long vowels are slightly diphthongised. Especially the high vowels /iː/ and /uː/ which are often narrowly transcribed in phonetic literature as diphthongs [ɪi] and [ʊu].

"Long" and "short" are relative to each other. Because of phonological process affecting vowel length, short vowels in one context can be longer than long vowels in another context.[21] For example, a long vowel followed by a fortis consonant sound (/p/, /k/, /s/, etc.) is shorter; reed is thus pronounced [ɹiːd̥] while heat is [hiʔt].

Conversely, the short vowel /æ/ becomes longer if it is followed by a lenis consonant. Thus, bat is pronounced [b̥æʔt] and bad is [b̥æːd̥]. In natural speech, the plosives /t/ and /d/ may be unreleased utterance-finally, thus distinction between these words would rest mostly on vowel length.[20]

In addition to such length distinctions, unstressed vowels are both shorter and more centralised than stressed ones. In unstressed syllables occurring before vowels and in final position, contrasts between long and short high vowels are neutralised and short [i] and [u] occur (e.g. happy [ˈhæpi], throughout [θɹuˈaʊʔt]).[22] The neutralisation is common throughout many English dialects, though the phonetic realisation of e.g. [i] rather than [ɪ] (a phenomenon called happy tensing) is not as universal.

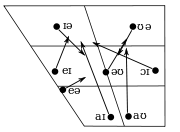

| Diphthong | Example | |

|---|---|---|

| Closing | ||

| /eɪ/ | /beɪ/ | bay |

| /aɪ/ | /baɪ/ | buy |

| /ɔɪ/ | /bɔɪ/ | boy |

| /əʊ/ | /bəʊ/ | beau |

| /aʊ/ | /baʊ/ | bough |

| Centring | ||

| /ɪə/ | /bɪə/ | beer |

| /eə/ | /beə/ | bear |

| /ʊə/ | /bʊə/ | boor |

Before World War II, /ɔə/ appeared in words like door but this has largely merged with /ɔː/. "Poor" traditionally had /ʊə/ (and is still listed with only this pronunciation by the OED), but a realisation with /ɔː/ has become more common, see poor-pour merger.[23]. In the closing diphthongs, the glide is often so small as to be undetectable so that day and dare can be narrowly transcribed as [d̥e̞ː] and [d̥ɛː] respectively.[24]

RP also possesses the triphthongs /aɪə/ as in ire and /aʊə/ as in hour. Different possible realisations of these diphthongs are indicated in the following table: furthermore, the difference between /aʊə/, /aɪə/, and /ɑː/ may be neutralised with both realised as [ɑː] or [äː].

| As two syllables | Triphthong | Loss of mid-element | Further simplified as |

|---|---|---|---|

| [aɪ.ə] | [aɪə] | [aːə] | [aː] |

| [ɑʊ.ə] | [ɑʊə] | [ɑːə] | [ɑː] |

Not all reference sources use the same system of transcription. In particular:

- /æ/ as in trap is also written /a/.

- /e/ as in dress is also written /ɛ/.[25]

- /ɜː/ as in nurse is also written /əː/.

- /aɪ/ as in price is also written /ʌɪ/.

- /aʊ/ as in mouse is also written /ɑʊ/

- /eə/ as in square is also written /ɛə/, and is also sometimes treated as a long monophthong /ɛː/.

Most of these variants are used in the transcription devised by Clive Upton for the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary (1993) and now used in many other Oxford University Press dictionaries.

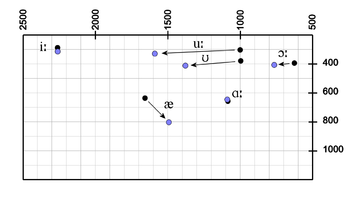

Historical variation

Like all accents, RP has changed with time. For example, sound recordings and films from the first half of the 20th century demonstrate that it was usual for speakers of RP to pronounce the /æ/ sound, as in land, with a vowel close to [ɛ], so that land would sound similar to a present-day pronunciation of lend. RP is sometimes known as the Queen's English, but recordings show that even Queen Elizabeth II has changed her pronunciation over the past 50 years, no longer using an [ɛ]-like vowel in words like land.[26]

The 1993 Oxford Dictionary changed three main things in its description of modern RP, although these features can still be heard amongst old speakers of RP. Firstly, words such as cloth, gone, off, often were pronounced with /ɔː/ (as in General American) instead of /ɒ/, so that often sounded close to orphan (See lot-cloth split). The Queen still uses the older pronunciations[27], but it is rare to hear them on the BBC any more. Secondly, there was a distinction between horse and hoarse with an extra diphthong /ɔə/ appearing in words like hoarse, force, and pour.[28] Thirdly, final y on a word is now represented as an /i/ - a symbol to cover either the traditional /ɪ/ or the more modern /iː/, the latter of which has been common in the south of England for some time.[29]

Before World War II, the vowel of cup was a back vowel close to cardinal [ʌ] but has since shifted forward to a central position so that [ɐ] is more accurate; phonetic transcription of this vowel as ‹ʌ› is common partly for historical reasons.[30]

In the 1960s the transcription /əʊ/ started to be used for the "GOAT" vowel instead of Daniel Jones's /oʊ/, reflecting a change in pronunciation since the beginning of the century.[31] Joseph Wright's work suggests that, during the early 20th century, words such as cure, fewer, pure, etc. were pronounced with a triphthong /iuə/ rather than the more modern /juə/.[32]

The change in RP may even be observed in the home of "BBC English". The BBC accent of the 1950s was distinctly different from today's: a news report from the 1950s is recognisable as such, and a mock-1950s BBC voice is used for comic effect in programmes wishing to satirize 1950s social attitudes such as the Harry Enfield Show and its "Mr. Cholmondley-Warner" sketches. There are several words where the traditional RP pronunciation is now considered archaic: for example, "medicine" was originally said /ˈmedsɪn/ and "tissue" was originally said /ˈtɪsjuː/.[33]

Comparison with other varieties of English

- Like most varieties of English outside Northern England, RP has undergone the foot-strut split: pairs like put/putt are pronounced differently.[34]

- RP is a broad A accent, so words like bath and chance appear with /ɑː/ and not /æ/.[35]

- RP is a non-rhotic accent, meaning /r/ does not occur unless followed immediately by a vowel. Pairs such as father/farther, pawn/porn, caught/court and formally/formerly are homophones.[36]

- RP has undergone the wine-whine merger so the sequence /hw/ is not present except among those who have acquired this distinction as the result of speech training.[37] R.A.D.A. (the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art), based in London, still teaches these two sounds as distinct phonemes. They are also distinct from one another in most of Scotland and Ireland, in the north-east of England, and in the southeastern United States.[37]

- Unlike many other varieties of English language in England, there is no h-dropping in words like head or horse.[38]

- Unlike most southern-hemisphere accents of English, RP has not undergone the weak vowel merger, meaning that pairs such as Lenin/Lennon are distinct.[39]

- Unlike most North American accents of English, RP has not undergone the Mary-marry-merry, nearer-mirror, or hurry-furry mergers: all these words are distinct from each other.[40]

- Unlike many North American accents, RP has not undergone the father-bother or cot-caught mergers.

- RP does not have yod dropping after /n/, /t/, /d/, /z/ and /θ/ and has only variable yod-dropping after /s/ and /l/. Hence, for example, new, tune, dune, resume and enthusiasm are pronounced /njuː/, /tjuːn/, /djuːn/, /rɪˈzjuːm/ and /ɪnˈθjuːziæzm/ rather than /nuː/, /tuːn/, /duːn/, /rɪˈzuːm/ and /ɪnˈθuːziæzm/. This contrasts with many East Anglian and East Midland varieties of English language in England and with many forms of American English, including General American. In words such as pursuit and evolution, both pronunciations (with and without /j/) are heard in RP.

There are, however, several words where a yod has been lost with the passage of time: for example, the word suit originally had a yod in RP but this is now extremely rare.

- The flapped variant of /t/ and /d/ (as in much of the West Country, Ulster and most North American varieties including General American and the Cape Coloured dialect of South Africa) is not used very often. In traditional RP [ɾ] is an allophone of /r/ (used only intervocalically).[41]

See also

- Accent (linguistics)

- Prestige dialect

- The Queen's English Society

- English language in England

- English spelling reform

- Estuary English

- General American

- Cockney

- Prescription and description

- U and non-U English

Audio files

- Blagdon Hall, Northumberland

- Burnham Thorpe, Norfolk

- Harrow

- Hexham, Northumberland

- London

- Newport, Pembrokeshire

- Teddington

Notes

- ↑ this term is more often used to refer to written Standard English, as in the Queen's English Society.

- ↑ Received Pronunciation

- ↑ Wells (1970:161)

- ↑ McDavid (1965:255)

- ↑ Hudson (1981:337)

- ↑ Fishman (1977:319)

- ↑ Jones (1917:ix)

- ↑ Ellis, Alexander J., 1869, On early English pronunciation, Greenwood Press: New York, (1968), p. 23.

- ↑ DuPonceau, Peter S., 1818. "English phonology; or, An essay towards an analysis and description of the component sounds of the English language." Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 1, 259-264 (p. 259).

- ↑ Wyld, Henry C. K., 1927. A short history of English (3rd edn), Murray: London, p. 23

- ↑ British Library website, "Sounds Familiar?" section.

- ↑ Crystal (2003:54-55)

- ↑ David Crystal, The Stories of English, Penguin, 2005, pages 243-244

- ↑ Schmitt (2007:323)

- ↑ http://www.bl.uk/learning/langlit/sounds/case-studies/received-pronunciation/

- ↑ Jones (1917:viii)

- ↑ Gladstone's speech was the subject of a book The Best English. A claim for the superiority of Received Standard English, together with notes on Mr. Gladstone's pronunciation, H.C. Kennedy, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1934

- ↑ Roach (2004:240-241)

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Roach (2004:240)

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 GIMSON, A. C. ‘An Introduction to the pronunciation of English,' London : Edward Arnold, 1970.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Roach (2004:241)

- ↑ Roach (2004:241, 243)

- ↑ Roca & Johnson (1999:200)

- ↑ Roach (2004:240)

- ↑ Schmitt (2007:322-323)

- ↑ Language Log. "Happy-tensing and coal in sex". http://itre.cis.upenn.edu/~myl/languagelog/archives/003859.html.

- ↑ The Queen's speech to President Sarkozy "often" pronounced at 4:44

- ↑ Joseph Wright, English Dialect Grammer, p.5, section 12. The symbols used are slightly different. Wright classifies the sound in fall, law, saw' as /oː/ and that in more, soar, etc. as /oə/

- ↑ The Dialects of England, Peter Trudgill, Blackwell, Oxford, 2000. p.62

- ↑ Roca & Johnson (1999:135, 186)

- ↑ http://www.phon.ucl.ac.uk/home/wells/rphappened.htm Point 3

- ↑ Joseph Wright, English Dialect Grammar, p.5, section 10

- ↑ David Crystal, The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language, Cambridge University Press, 1995, p.307

- ↑ Wells (1982), pp. 196ff

- ↑ Wells (1982), pp. 203ff

- ↑ Wells (1982), p. 76

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Wells (1982), pp. 228 ff

- ↑ Wells (1982), pp. 253 ff

- ↑ Wells (1982), pp. 167 ff

- ↑ Wells (1982), p. 245

- ↑ Wise, Claude Merton. Introduction to phonetics. Englewood- Cliffs, 1957.

References

- Crystal, David (2003), The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language (2 ed.), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521530334

- Elmes, Simon (2005), Talking for Britain: A journey through the voices of our nation, Penguin Books Ltd, ISBN 0140515623

- Fishman, Joshua (1977), ""Standard" versus "Dialect" in Bilingual Education: An Old Problem in a New Context", The Modern Language Journal 61 (7): 315–325, doi:10.2307/324550, http://jstor.org/stable/324550

- Hudson, Richard (1981), "Some Issues on Which Linguists Can Agree", Journal of Linguistics 17 (2): 333–343, doi:10.1017/S0022226700007052

- Jones, Daniel (1917), English Pronouncing Dictionary, London

- de Jong, Gea; McDougall, Kirsty; Hudson, Toby; Nolan, Francis (2007), "The speaker discriminating power of sounds undergoing historical change: A formant-based study", the Proceedings of ICPhS Saarbrücken, pp. 1813–1816

- McDavid, Raven I. (1965), "American Social Dialects", College English 26 (4): 254–260, doi:10.2307/373636, http://jstor.org/stable/373636

- Roach, Peter (2004), "British English: Received Pronunciation", Journal of the International Phonetic Association 34 (2): 239–245, doi:10.1017/S0025100304001768

- Roca, Iggy; Johnson, Wyn (1999), A Course in Phonology, Blackwell Publishing

- Schmitt, Holger (2007), "The case for the epsilon symbol (ɛ) in RP DRESS", Journal of the International Phonetic Association 37 (3): 321–328

- Wells, J.C. (1970), "Local accents in England and Wales", Journal of Linguistics 6 (2): 231–252, doi:10.1017/S0022226700002632

- Wells, John C. (1982), Accents of English I: An Introduction, Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-29719-2, http://books.google.com/?id=UJQwf05yzqYC

External links

- B.B.C. page on Upper R.P. as spoken by the English upper-classes

- Sounds Familiar? – Listen to examples of received pronunciation on the British Library's 'Sounds Familiar' website

- 'Hover & Hear' R.P., and compare it with other accents from the UK and around the World.

- Whatever happened to Received Pronunciation? - An article by the phonetician J. C. Wells about received pronunciation

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||